The too easy answer is that I love horror.

My first loves in computer games were all horror. In fact gaming led me to horror before I’d fully realized what genres were and that I had to pick some in order to define my tastes.

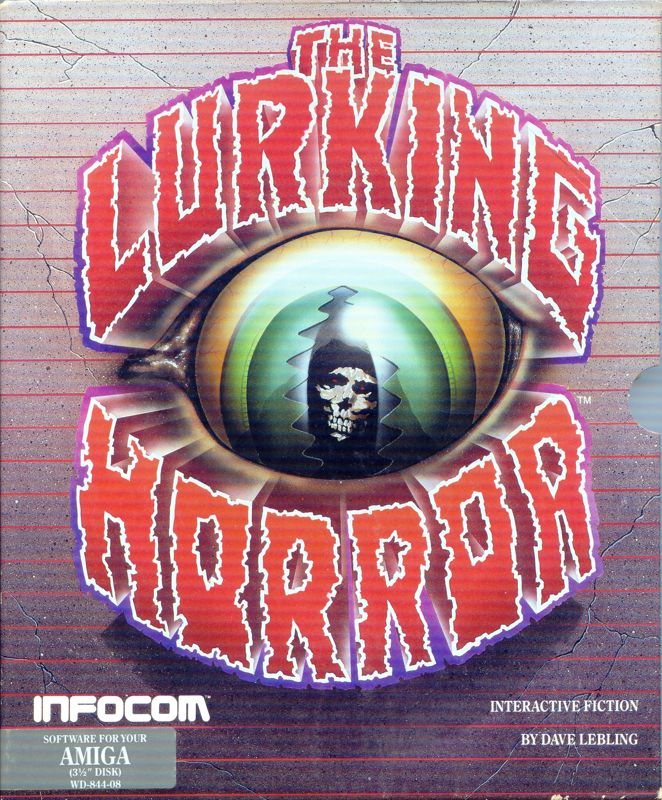

Lurking Horror, Infocom’s big nod to Lovecraft and M.I.T. Alongside their detective title Suspect this was my favorite classic text game growing up. Its setting of an isolated college campus after hours in the midst of a blizzard was intense. Its inhuman floor-waxing janitor used to haunt my dreams — even before I played the game I was aware of his existence from skimming hint pages in Amstrad Action magazine.

Electric Dream’s CPC version of Aliens — still the scariest game I’ve ever played. The game was so intense that we’d frequently have to hit the pause button — which smashed some blast doors over the action and played the boppy title music — and sit it out for a few minutes.

To be honest, most of the early games I played were basically horror. A plethora of maze games and abstract arcade games where death was frequent and unrelenting. Some were accidentally creepy — Spikey Harold aimed for “cute hedgehog adventure” and ended up with an early slice of survival horror because its two main colors were black and red. Everything the poor hedgehog below touched was instant death and it was brutal. A literal nightmare:

One of the first games I made myself was a BASIC horror game using a homemade text adventure engine that was somewhat less sophisticated that Infocom’s. All I can remember about is that at one point you spied on some werewolves having sex (they started off human, then got hairy.) I think it was called “Jessica.bas“. Sidenote: it’s hard to unstate how creepy games were back when your first contact was typing out their short, evocative filenames.

And outside of games my interests always led me to horror:

Tangentially via Surrealism — checking out the art galleries of Oostende was always the high point of the annual summer vacation. Thank you Magritte for this nightmare fuel:

and to Dali & Bunuel introducing me to the collision of metaphors.

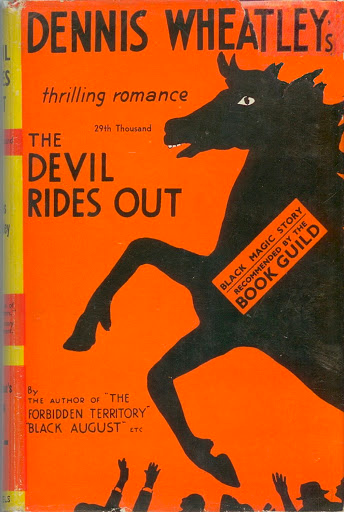

Then explicitly through the mildewed Satanic horror novels I found in a cupboard at my nana’s (tucked away by my uncles in a previous generation)

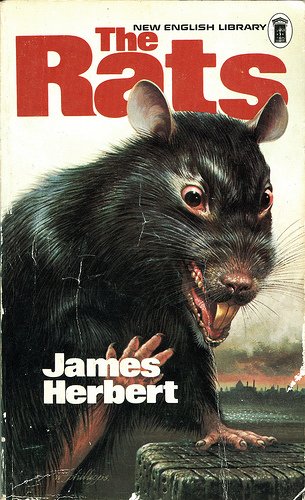

Working up to my local library’s cursed and dog-eared copy of James Herbert’s The Rats (Horribly, mortally terrifying it has given me a lifelong fear of rodents.)

Then graduating to the same library’s Clive Barker books (scary, but also a bit sexy?)

Horror Movies came later, once I was old enough to be allowed to go pick our Friday night video from the local gas station that doubled as a video rental destination. My younger brothers and I always picked a movie based on how gross or the cover was. We had no real idea that the Scanners sequels were not as good as the original and to be honest we didn’t really absorb who was making these movies.

My pick of Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch was my first Burroughs experience and meant I didn’t get to choose the next week. Exploding heads were fine but talking assholes were a step too far for my brothers.

I kept going from there. To the real Burroughs. To Bataille’s Story of the Eye. I read imported copies of Cinefantastique magazine. Ballard’s Atrocity Exhibition. Ellen Datlow’s horror anthologies. De Sade’s gothic horrors were more math than horror, but that worked for me. Alex Cox’s weekly BBC2 double-bill Moviedrome (carefully taped on the rotating set of five VHS tapes in our house) introduced me to the stuff that you couldn’t see elsewhere and made it pretty clear that the membrane between arthouse and midnight movies was permeable.

So years later, when I got to work on horror games professionally although it was mostly thanks to forces outside of my control, it was fair to say I had led myself to it as much as been led. I had very strong opinions about what was interesting about interactive horror. I got to express some of them with Silent Hill: Shattered Memories and there were one or two that didn’t make it out the door.

Which brings us to the present day. I am now slightly better known for detective stories and thrillers (granted with a gothic streak.) Disregarding a general love for the stuff and my childhood indoctrination, why horror now? Why with this game?

With Her Story and Telling Lies, I’ve been exploring what kinds of stories we can tell when we put more of the work on the player’s imagination. Both these stories work on ideas that are off screen, outside the on screen action. Both were efforts to tell stories about people’s inner lives via performance and subtext. Both tried to draw the player in and make them more complicit and involved in the narrative without the ‘standard’ direct cause-and-effect of most videogames.

The engine for these imagination-driven games comes from our primal desires — our curiosities, our need to peek into other people’s skulls and understand what is inside. A part of these games was the idea of pushing back against the player — their screen reflections and audio tricks were designed to prod at a player’s suspension of disbelief in order for it to prod back.

So in thinking where to go next, it was inevitable that horror was on the menu. Exploring characters’ inner lives, having the player’s imagination become enmeshed with the game’s story? With horror we can crack that skull open and have the inner life leak out onto the screen. The player’s desires and imagination can warp the story and have themselves warped back.

I am particularly interested in a kind of horror that exists on the periphery of your vision, one that once injected into your brain isn’t easily flushed out when you turn the screen off. For this to work the real horror has to take place in those dark places off screen, the places where I’ve been working diligently in Her Story and Telling Lies. This time when we prod your suspension of disbelief, it’s going to hurt.

To be first in line to get your skull cracked open, wishlist Project A███████ here.

Also, join our newsletter for monthly roundups and occasional ghostly hints.