. . . In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

—Suarez Miranda, Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV,Cap. XLV, Lerida, 1658

The above is a cracking Borges short short story that preceded digital technology. In writing it, Borges did not have access to Google Maps and had played none of the videogames that would split their gameplay time between a Map View and a World View. He was unaware that, e.g.

- When playing Super Metroid or Silent Hill 2 it is the case that a lot of the player’s more important gameplay decisions occur on the map screen itself. In fact, players of O.G. Silent Hill games usually spend around 30% of their playtime on the map screen.

- In most exploration focused roleplaying games the player is as much a cartographer as the are a warrior or mage, even if the fiddly business of drawing a map is automated in more recent games.

- In Zelda: Breath of the Wild some of the more amusing side quests require players to chart and triangulate locations on their map in order to discover secrets.

But of course the joke that Borges is making is redundant in a videogame where the ‘world’ and its ‘map’ are both inventions and abstractions. Or perhaps it’s very prescient.

As someone who is obsessed by the idea of story and exploration in videogames, the biggest leap I made was in synthesizing the idea of a world in which one explored to discover story content (audio logs, diary pages) and the story content itself. What if instead of exploring and mapping a space in order to find a jigsaw story, I was instead exploring and mapping the jigsaw story itself? That was the idea behind Her Story, expanded in Telling Lies and now being heavily re-factored in Project A███████.

In this project we are further entrenching ourselves in the idea of fusing the Map & the Territory. A few games have encouraged us along this way. Simogo’s Device 6 is a marvelous example where text and level design are fused in a manner reminiscent of concrete poems. But before that, David Shute’s Small Worlds was the game I would always return to for its incredible implementation of the idea.

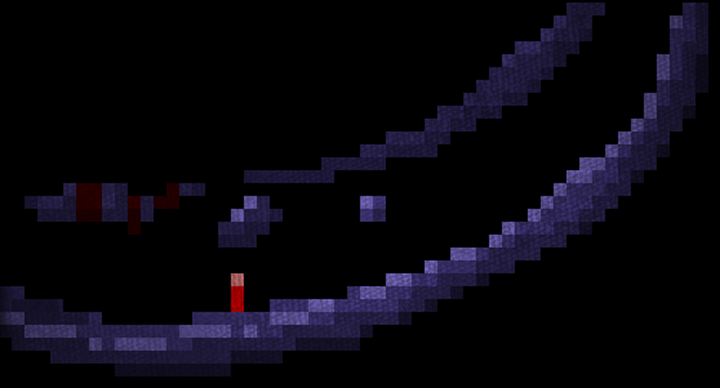

Small Worlds sells everything that is marvelous about exploration in videogames and everything that is marvelous about Metroid games — all in a tiny package! If you haven’t already, go play Small Worlds now, before I spoil it.

You start as a little character in a small space and naturally head out — and jump! And explore, with all the knotted pleasures of a ruined Metroid type setup. And as you explore, the magic starts to happen — the pleasure of filling out a map in Metroid, of understanding the big picture of the layout, occurs in the same view as your character control! As the camera effortlessly zooms out in sync with your exploration these two perspectives on the game are simultaneously experienced. The world becomes the map.

The game’s subtractive design means there are no other verbs to complicate or obscure what is happening. You walk and jump, explore, and build up a cohesive picture of the world. The map and the world are one and your interaction with them as a player is fluid. It’s a pure hit of exploration and a testament to the power of zooming to bridge the divide between the map and the territory. The most Borgesian pixel art game.

–Sam