The following is an edited transcript of a conversation between Natalie Watson (our Associate Producer) and Jeff Petriello (our Producer). Listen to that convo here:

An Introduction

Jeff: Hi Natalie!

Natalie: Hi Jeff!

J: Where are you?

N: I’m in Brooklyn right now. I left the house for the first time today because I was under a 14-day quarantine and walking is something I haven’t done in two weeks. Turns out it feels pretty good when you walk.

J: I’m in Provincetown for the summer, and when I first got here I started biking again. I was basically not moving at all in Brooklyn, and it’s done wonders for my well-being.

But yeah, this is our first attempt at doing a production blog for the project that we’re working on (AKA Project A███████). Do you want to introduce yourself? Maybe explain why we’re doing this?

N: My name’s Natalie, I’m the Associate Producer here at Half Mermaid. I used to be a game critic at Waypoint, now Vice Games, and then I transitioned into game dev. I’m working for Sam with Jeff and Connor and making something very, very cool.

J: I’m Jeff Petriello, I’m the producer at Half Mermaid. I came into this after graduating from the NYU Game Center, getting my degree in Game Design, and after almost a decade working in production for film and digital media. So the fact that we’re making another live-action, full-motion video game in Sam Barlow’s repertoire is a perfect blend of my experience and my education.

We just figured we want to give people a little bit of insight into our process here. I know it could be pretty mysterious, so we’re gonna try it and see if it works and see if people are interested in it.

We just figured we want to give people a little bit of insight into our process here.

– Jeff

I would love to eventually have a dialogue with anyone out there who cares, wants to ask questions or get further insight into this industry or into the game scene in Brooklyn. Though, we’re a little bit spread out. You just moved. You’re moving.

N: I’m moving, yeah, I’m in a transitional phase between New York and Los Angeles. So I will be leaving the Brooklyn game scene for another game scene, but I think I’m still a part of it. Just from a distance.

J: Yeah, I think it will always be in your heart. I’m glad you’re going out to LA. We have a lot of overlap with the film industry, so it’ll be really awesome to have you there.

N: Yeah, I’m excited to hopefully start getting into what the scene looks like. It’s been a while since I’ve lived there. I’m very excited about making some new friends out there in our industry.

Frida, Film, & 80s Horror

J: So in the mornings we have a Zoom meeting and we talk a lot about things that we watched or read or played that are influencing how we’re thinking. I wanna bring a little of that into this blog. Anything that you have the opportunity to consume this week that really stuck with you?

N: I’ve been thinking a lot about the Frida Khalo movie with Salma Hayek (Frida, by Julie Taymor). It’s not totally in line with what our vision is, but I found it so interesting. It’s a very weirdly done movie. It’s more kooky and artistic than I remembered it, and there’s a lot of transitional scenes where they actually bring Frida Kahlo’s art to life. They’ll have dancing skeletons or different things that are enacting her paintings as a miniature scene. I’ve been thinking a lot about that when thinking about how we get weird or how we get strange in our own filming and what transitions could end up being like for us.

We were talking the other day about Netflix suggestions and how the movie thumbnail changes based on your preferences. For some reason, my icon for the movie about Frida Kahlo is Antonio Banderas, who has a 30-second scene and isn’t in the rest of the film at all. But for some reason, Netflix thinks that I’m coming to Frida for Antonio Banderas.

For some reason, Netflix thinks that I’m coming to Frida for Antonio Banderas.

– Natalie

J: I have to say, I just watched Evita last week for the first time. He’s the best part of that movie, besides the production value. No shade to Madonna, but…

N: What have you been watching or consuming this week that has been inspiring to you?

J: Two big things: I finished a book called The Watcher. It’s a horror novel from the mid-80s by Charles Maclean. And it’s really… It was terrifying. I had never really read horror. This is something that I’ve been getting into since we started working on this project, and it was just so interesting to read and experience what I normally consume visually. It gave me the feels of Rosemary’s Baby or The Shining. It was just cool to read something like that and see how it functions in prose. So, I really enjoyed that.

Objects, Abstraction, & Spaceships

The other big thing this week was a play through Tacoma designed by Steve Gaynor and Nina Freeman for Fulbright. I plowed through it in three hours, but I really enjoyed it. It was very cinematic in a lot of ways. I’m super into this vibe of shorter games – games that people can consume in or around the amount of time that they consume a movie. I know that’s a really difficult thing to design and have it feel great and satisfying, and I think Tacoma did a really interesting job of it. The writing was incredible, the voice acting was incredible, the gameplay was really intuitive. Navigating felt good. I just was very impressed by it. I haven’t played Gone Home, don’t come for me.

N: That’s another one that you can actually finish in a sitting. Especially you, if you’re not checking every item.

J: Yeah, Sam was like “How did you finish it in three hours?” and I was like, “How did you not finish it in three hours?” And he said, “Well, I was picking up every single object” and I don’t do that. I was burned from Skyrim. I get absolutely nothing out of it.

I mean, I did pick up a few items in Tacoma. I thought the medicine was really interesting. I thought all of the 3D models that they did were beautiful, though I question the effort that was put into that – what it contributes in such a short or narrow scope story, one that you can really finish in that amount of time. Where do you put your energy as a developer and a designer?

I think that’s a really interesting question. By no means do I think they did anything wrong or anything, but where you put the effort, where you put the detail, I think says a lot to you and the player about what you’re considering important. And obviously, it was very important to them to have a very realistic environment, one that you could fully explore, one that you could pick up every single object. But for me as a player, that doesn’t do it for me.

N: Well, I understand if the reference point is Skyrim, because I feel like objects in AAA open world games are so incredibly overwhelming. Especially Skyrim, where you have sonnets and poems and random ballads and all this extra material that is supposed to deepen the immersion of the world, but ends up just being such an overwhelming amount of information that it’s hard to internalize any of it.

I find that, especially in smaller games that lean towards the Immersive Sim genre, like Gone Home or Prey, the found object is so much more compelling to me. In a tight game, the object has to have some value, it has to tell a story. Whereas in a game like Skyrim, in every object there are a thousand stories that are being told.

Would you find yourself ever going back and playing Tacoma again and spending more time with found objects? Or could see yourself playing Gone Home in the future?

J: I definitely wanna play Gone Home. I had a good time with Tacoma and it’s so important.

N: It’s worth it.

J: I think you brought up a really interesting point in the difference between objects in the two different genres. There were limited instances in Tacoma where I found what I picked up to be interesting.

For instance, I’ll go back to the medicine. Opening someone’s drawer and seeing what prescription they have is a very telling moment. Now I’m getting insight into you as a character: what you’re dealing with physically, what the state of your health is. That tells me something new about you that I’m not getting through the story of the game.

Generally speaking the found objects in Tacoma were way more interesting to me in the personal quarters of each of the characters, where you’re going into their literal bedrooms and you’re seeing those private objects that help build that character’s background and existence for you as a player. It was the other stuff that doesn’t really do it for me. I walk into someone’s bathroom and everyone has a glass, everyone has a toothbrush. That doesn’t provide me with any new information. All it tells me is this is a bathroom. I’m not learning anything new.

N: They wanted it to be, I think, more exploratory. You take the time to investigate what you want to.

I think there’s a lie we’re telling ourselves that this kind of exploration contributes to realism.

– Jeff

J: I think there’s a lie we’re telling ourselves that this kind of exploration contributes to realism. When I walk around the world, even if I’m in an environment where I could get away with picking up stuff that’s not mine, I don’t generally do that. I don’t walk around picking up random objects in the world and twirling them around in front of me. That’s not a real thing that I do. Yes, the object being there in existence, the quality of the model, definitely contributes to the realism of the game, but the interaction that you need to do with that object as a player is not realistic in any sense. I think we have to confront that.

Also, objects are gonna play a really important role in the project that we’re working on, so I think this is a really relevant conversation for us.

N: It’s true. I think the objects you’re talking about in terms of toothpaste and a glass in every bathroom is almost a direct response to the sort of environment that we’ve explored before – the bathroom environments that have had nothing but gun ammo in them. It’s pushing away from the disbelief or the un-immersion of finding health packs in every environment. Now you find the sort of menial, everyday stuff and it’s not as useful. It doesn’t have value in the sense that you’re not using it to complete something. You’re not using it in your game play. It’s there and it exists.

J: I also wanna mention for anyone else interested in this discussion that it deals very directly with issues of scope of abstraction in game design, which is something you can read a lot about with a quick Google. Deciding what’s going to be abstracted and what’s going to be simulated is constantly a question you need to ask yourself as a designer, so I think those decisions are really important.

But let’s talk a little bit about what we’ve been working on.

Homicide Detectives in the 70s

N: Yeah, I think one of the more interesting things to talk about combines what we are researching and what were some problems that we’ve solved this week.

One thing that’s been on my mind a lot is access to research and thinking about how heavily we’ve had to rely on your status as an NYU adjunct faculty member just to have access to a library with resources. Trying to find scholarly material on some of the time periods that we’ve been looking at, especially the 70s and late 60s, has been pretty difficult to navigate without having a research institution to lean on for resources.

The main thing I’ve been focusing on is detective investigations, how a homicide detective may navigate that situation. There’s a throwaway line in the protocol handbook I’m reading about securing the crime scene and how you need to have a sign in sheet for it so you can keep track of who’s coming in and out.

The reason for that is because so often there will be higher ranking members of the police force who will come to a crime scene just to be there because they feel the need to. Often that lends to a lot of contamination in the crime scene by politicians and high-ranking members of the force.

I read a lot of frustration in this. I don’t know what the right word is, but the display of importance or the act of just being present on a crime scene for media purposes or to show your rank or a role or whatever… it could be a big problem when it comes to the scene itself.

I’m learning a lot about how little integrity there is in a crime scene and how incredibly fragile it is from the moment somebody sets foot on the scene.

– Natalie

I’m learning a lot about how little integrity there is in a crime scene and how incredibly fragile it is from the moment somebody sets foot on the scene. So that was my less than fun fact in my research this week.

J: Cool. I mean, I haven’t touched any of that stuff. So it’s really fascinating to me.

N: Yeah, I should say that this is sourced from the 70s, so it’s not contemporary at all. But that throwaway line has stuck with me a lot, just thinking about who would wanna make themselves feel important.

J: It’s terrifying a little bit.

N: Yeah, it’s really fucked up.

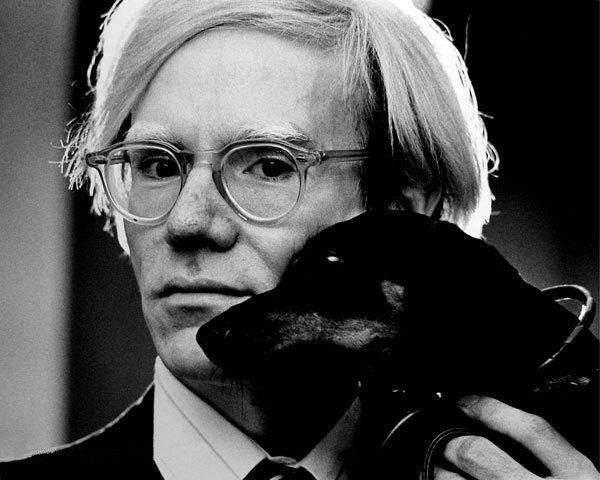

Art & Andy Warhol

J: So if you have been following our project, which is available to wishlist on steam if you search for “Project A,” you will find it’s very mysterious. But one of the clues that we have up there is “1971” and “NYC”, so I don’t think I’m spoiling anything by saying I’ve been looking into what’s been going on in NYC at that time, and the art scene there is really awesome.

Andy Warhol is at the end of his high point of being the social king of NYC then. So I’ve been doing research into that, and I think one of the things that stuck out to me is how swiftly he changed his personality in the late 60s when The Factory opened. The Factory is his studio after he discovers he needs bigger space and wants to work more collaboratively. He opens up this place where everyone is kind of welcome. It really attracts a lot of crazy characters, a lot of drugs, a lot of parties, a lot of people just living to extremes. He always wanted to surround himself with people on the extreme.

But friends and people that were close to him describe this six-month period in 1968 where he basically changes his entire personality. He goes from being this sort of innocent with drawings that are childlike in their simplicity of line, and he starts doing all this big massive reproduction. That’s why it’s called The Factory. It literally becomes an art factory, and part of that is this new identity. He assumes this cold, detached personality of essentially having no personality. He just rejects any and all accountability really for what he’s doing. People ask him “What does your art mean?“ and he just says “ It doesn’t mean anything. It gives me something to do.” He has the shtick of supreme detachment, and that was crafted. That was entirely designed.

It was a PR tactic for sure. Warhol, almost more than any other 20th century artist, is really the prophet of our times in the sense of how people present themselves online. If we look at social networks, we look at Instagram, we look at Only Fans, we look at whatever it is, he was really talking about and addressing a lot of that self-promotion and 15 minutes of fame. Obviously, he was the spokesperson for that, so I’ve been going back and looking at him as a sort of primordial archetype of that culture. Realizing that was so purposeful is really interesting to me and a very sharp contrast to the filmmaking that he winds up doing in the early 70s, which are these hyper, non-directed looks at moments in time, just capturing people kissing, capturing people eating, capturing people getting a haircut. They’re almost impossible to watch because of their length.

The films are, in my opinion, very much about something. They’re very much about humanity and cinematography and what it means to be able to observe and replay an actual person living, which is not casual at all.

I’m becoming more of a Warhol fan the more I learn about him. Though I think in a way, he’s a very dangerous artist. So I still have my reservations, but yeah, that’s really what stuck with me this week.

N: Yeah, that’s interesting.

I feel like your analogy to Twitter and Instagram is real. Only Fans is a different thing altogether, because you’re dealing with paid labor, but when considering how so much of pop culture is about overexposure right now…it’s like we think we know so much about the lives of the people that we look up to. I don’t know any influencers that I would say I look up to, but people look up to influencers.

We think we know so much about their lives, and so much about their day-to-day, but when we think about the celebrities or culture icons of Andy Warhol’s time or before – like when you find candid footage of Marilyn Monroe – it’s so hard to wrap our brains around her because all of our images of her are performance.

J: Exactly.

N: The candid or day-to-day is such a rare, protected sacred artifact that when we find footage like that it’s totally disorienting to our image of them. Warhol knows he knows this and completely pulls back. It has to be a reason that he became such an icon. There is so much behind closed doors, so much that he just wouldn’t let on no matter what.

There’s an interview with him and Edie Sedgwick on Letterman or some late night talk show and he doesn’t speak. He speaks maybe one time and Edie just answers all the questions for him, or he’ll whisper in her ear and she’ll answer for him. No one is doing that now. Who feels out of reach to us now?

Who feels out of reach to us now?

– Natalie

J: Yeah, I think that’s a great insight.

I think the reason why I called Warhol dangerous is related to this. I have to do more research, but there’s this creeping sensation I have that part of this detachment is an obsessive desire to separate your actions from the consequences of your actions. It’s saying “I made this thing. Don’t ask me questions about it. I don’t care what it did in the world, what it does to the world,” even though he knows it’s really doing stuff. It’s a complete and utter rejection of accountability for the consequences of what you are putting in the world, and that is dangerous to me. We don’t have time for that right now.

N: We really don’t have time for that right now.

J: We need people to think about what they are saying and what they are doing and what the impact of it is. Warhol lives at the time before people could publicly react to what famous people were saying and hold them accountable to it. He built that ivory tower and he lived in and fought for it. I think so much of what’s going on now in culture, like that stupid Harper’s Bazaar letter that all those people signed, is that tower is falling apart and all the people that were living in it are really mad about it. I think Warhol helped get us there. I don’t care if you say you don’t care what you did. You did something. So that’s why I’m saying there’s a dangerous sensation that I get when we talk about him and we look at what he did.

At the end of the day, he is a very great fine artist, and in many ways he was throwing up a mirror to how a lot of people were acting around him, the general cultural sentiment that was growing. He’s not the only one who did that. In fact, I think he amplified and showed us it and in many ways, I’m thankful for that. But we are past the point of you just saying, “I am making something and that’s it.”

N: Yeah, the public is not going to accept that anymore.

J: Well, I don’t want this to go on for so long that people don’t care at all, but this would be the point where I would love to answer any questions anyone had about what we were working on. So if you’re listening out there and wanna tweet at us or send us an email or message on any platform, let us know. I would be happy to do that.

I am @thebeff on almost every single social network.

N: I’m @nataliewatson on Twitter, you could find me there.

You can find our studio @halfmermaid on Twitter. You can email us at [email protected]

And this was really fun. I’m excited to do more of these!

Thanks for reading (or listening) to our first production blog. Be sure to wishlist Project A███████ on Steam and please send us feedback!